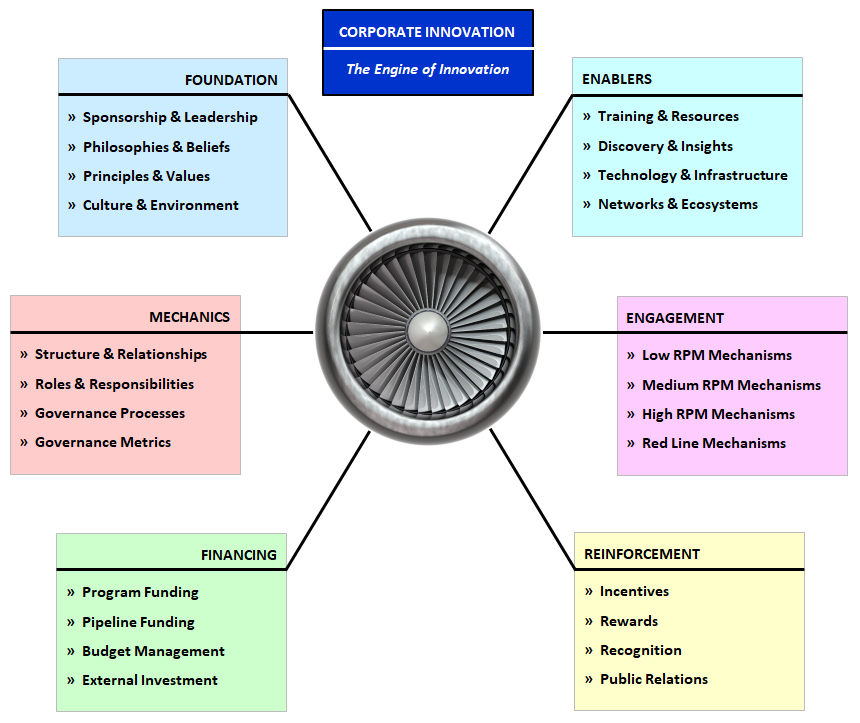

The following presents full details of the Responsive Innovation Engine Architecture and its twenty–one elements.

To jump directly to any one of these elements, please select from the list here...

In order for a Corporate Innovation program to be successful, the company's Board of Directors, CEO, and Executive Leadership Team must act in concert to do two things.

First, they must issue a mandate for innovation and for innovation–driven growth. Inside of any Corporate Innovation program, this mandate has to exist, and it has to originate at the highest levels of the organization. With this, its priority and gravity must be clearly communicated throughout the company, horizontally across every function, and vertically along every level. In some cases, other mandates, structures, roles, and processes may need to be altered to accommodate this mandate. Ultimately, it has to be given a level of priority in the organization to ensure it will be taken seriously and live a long life. Until the Executive Leadership Team has issued such a mandate, innovation will go nowhere. No amount of training, process, procedure, and so forth will make the company any more innovative. It is not until this mandate has been issued that the patterns for pursuing innovation will get laid down, the philosophy of innovation embedded, and ultimately, that innovation will happen in the business.

Second, the executive leadership team must pledge and act on its ongoing support for the people and groups who are to carry out the program. This will at times mean providing ‘air cover’ for the program and running interference for its projects in order to shield it against the forces of organizational momentum that – in the name of efficiency and immediate returns – otherwise seek to protect the status quo. This requires that the leadership team embraces a long term perspective and a healthy respect for the fact that the world around them is constantly changing and those changes will imminently demand the sort of exponential thinking that only comes from intentional innovation.

If an organization is to make truly impactful innovation a day–in and day–out reality in their business, they are going to have to adopt a fundamentally different set of philosophies about business and innovation. In particular, they must fully embrace each of the following three core philosophies:

This philosophy demands that innovation not be relegated to a core, elite team locked away in an ivory tower somewhere (though those teams have their place), but that it be democratized by giving everyone responsibility for it, and the right orientation and tools to deliver on it. It understands that achieving successful innovation across a business means that every area of the business must be fair game for innovation, whether it's in R&D, Product Development, Sales, Marketing, Operations, and, yes... even Executive Management. Only by embracing this philosophy will the organization be able to evolve and continue thriving and growing into the future. This being the case, there are three key practices that accompany this philosophy – things companies must do to make this a reality. They are:

This philosophy understands that innovation is not a random act of creativeness, nor is it reckless abandon. There are practical and methodical approaches to innovation, just as there are for any other practice. These approaches significantly lower the level of risk associated with pursuing innovation, because they are intelligent about how they go about it, and they employ the most effective vehicle for doing so. There are two principles associated with the intelligent pursuit of innovation. These are:

This philosophy recognizes that, although ordinary incremental innovations are needed to gradually extend the business' current foundations of value, such a strategy is ultimately short lived. Over time, the world changes, markets change, technologies change, and so must the business and its offerings. What this means is that the fundamental underlying assumptions of the business model and the value proposition must be regularly reexamined and challenged, to see if they still hold up against current external realities. Inevitably the day will come when the argument that they do becomes increasingly weaker. Indeed, while a business may go through any number of business cycles with successive generations of the same value proposition, eventually the assumptions underlying that value proposition will give way to new realities, and the only viable path forward from there will be to abandon it and embrace a completely new one... one that is the breakthrough or disruption for that market space – and one that has the ability to carry the business into the future. But since new business models and value propositions take time to develop, implement, and scale, one has to proactively pursue these early on, even before they are needed. When this is well understood within the business, it will become clear that breakthrough innovations are necessary for Horizon 2, and disruptive innovations for Horizon 3, and there will come to be an ongoing mandate for pursuing these.

This also calls for a lean and responsive (agile) approach to innovation.

These are the three core business philosophies that a company must embrace if it is to deliver truly impactful innovations day–in and day–out. Similarly, if a Corporate Innovation program is to realize its fullest potential across the business, this set of philosophies must become deeply woven into the fabric of the program.

In a mature innovation organization, the organization will have reached a point where its values embrace the concepts of market relevance, long–term resilience, and overall market leadership. It may even have a formal statement of values indicating this in so many words. The organization will therefore operate according to certain principles reflecting those values.

Furthermore, if these truly are the organization's values, it will have put into practice the beliefs associated with the innovation philosophy espoused above, such as market orientation, design orientation, and methods for pursuing intelligent innovation and minimizing risk, including the use of discovery skills and business experimentation.

These are the essence of mature innovation values and principles. Each organization must codify these in whatever form is most meaningful and effective for its people.

While leadership initiates Corporate Innovation, and philosophy steers it, culture is what nurtures and sustains it.

Organizations who understand this are intentional about cultivating and nurturing not only a culture of innovation, but more importantly, a culture of relevance. What this really means is a culture that embraces change and uncertainty, and that constantly strives toward new levels of market connectedness and a more enlightened sense of purpose (see the Experiential Workplace Framework for more on this).

Unfortunately, this has traditionally been the exception to the rule. For the past century, businesses have been trying to apply Modern Management Theory in a relentless pursuit of efficiency, productivity, and lean, all aimed ultimately at maximizing margins. This has produced cultures that inherently presume the world will go on working the way it currently does – that our futures can be extrapolated from our present, and that we should therefore expend our energies and efforts toward finding new ways to maximize the capitalization of those patterns. But that is not the reality of the world we live in. Instead, society, technology, markets, and the world at large are changing at a rapid pace. The world will not go on – indeed, is not going on – working the way it currently does, and our futures cannot be predicated on our present.

This requires the sort of nonlinear, exponential thinking that expects the world to change, and is willing to embrace that reality and act on it. But such a change in thinking does not come without a change in culture. Therefore, the successful pursuit of Corporate Innovation requires a shift in culture, if not for the entire organization, then at least for the parts charged with delivering innovation–driven growth (including the executive leadership team).* This culture must become one that fully embraces the uncertainty and changes imminently before it, that desires to find the offensive maneuvers it needs to respond accordingly, and that openly fosters the exploration, experimentation, and learning – even learning through constrained failure – needed to get there. It's a culture that creates an environment welcoming of the innovator's discovery skills – observing, questioning, networking, experimenting, and associating. Such a culture will engage a new generation of professionals on their own terms... hungry to live out a sense of purpose and meaning as they press forward into the future (a viewpoint shared by many Millennials). Change will invariably come about as a result of this program. Therefore, this culture is absolutely necessary if the company is to create an environment conducive to creative innovation and to breaking down the barriers and obstacles that will invariably be thrown in the way of these changes. One of the important ways it does this is by giving the organization a common language around innovation, and a common set of core values for innovation and growth. When these become woven into the corporate vernacular, they give innovation a ‘soul’... a presence... a persona... a face within the organization, and they become an integral part of the organization's way of life.

Finally, this need for cultural underpinnings cannot be overemphasized. Peter Drucker famously once said “Culture eats strategy for breakfast”. Mick Simonelli similarly stated that “Culture eats innovation for lunch.” So, while a good culture might survive a bad strategy a time or two (though not indefinitely), a good strategy never survives a bad culture! When a business hits hard times (and every business inevitably will), culture is what separates the survivors from the losers. Thus if a Corporate Innovation program is to thrive and produce the results it signed up for, it must have the cultural underpinnings it needs to support and nourish it over the long haul. A lack of this culture is a non–starter for success in Corporate Innovation.

* Note that even inside of great cultures, operational bifurcations can and do occur. This gives rise to the ambidextrous organization with structural ambidexterity – parts of the company are focused on operational efficiency for today and parts are focused on innovation–driven growth for tomorrow. This is not always a bad thing, and in some cases can be thought of as “flying the plane on both wings”.

Successful Corporate Innovation requires its own unique set of organizational structures. Just as trying to get water to flow from Point A to Point B requires a plumbing structure, or trying to get energy to flow from Point A to Point B requires a wiring structure, trying to get new ideas to flow from conceptualization to commercialization requires a particular set of organizational structures. Without these structures, the ensuing innovation processes will be unable to ‘flow’, and individual efforts will hit dead–ends and roadblocks with no easy way around or over them. This means that projects will go unexecuted and the needed results unrealized. For this reason, having the right structures in place is imperative.

Perhaps the most fundamental structure question the organization will have to address is where to locate its ‘innovation function’ – does it centralize innovation, decentralize innovation, or do both. The first utilizes a dedicated core innovation team to drive and execute all innovation projects. The second rolls out innovation as a core distributed competency, and tasks individual functional groups and business units with making a certain percentage of their projects true ‘innovation projects’. The third uses a hybrid of both approaches. No one approach will be right or wrong for every situation. There are well–understood pros and cons to each approach, and each company must carefully consider its current organization, its culture, its capabilities, its industry and markets, and any number of other factors to determine which approach might be best suited for it.

The following matrix lays out some of the implications for centralized versus decentralized approaches. As can be seen, for each stage of the innovation process – front end (ideation), mid zone (strategizing), and back end (commercialization) – this decision has important implications for where certain commercial and technical activities will take place (e.g. Chief Innovation Officer's office versus front line business units, etc.).

In more ‘traditional’ organizations, it is usually advantageous to centralize innovation as a stand–alone function, as such groups will be less encumbered with the current way of doings things and can more easily “break away from the pack”. In more ‘progressive’ organizations, it is often advantageous to either decentralize innovation or else take a more hybrid approach. A large number of businesses considered ‘most innovative’ often employ a hybrid approach where Horizon 1 initiatives take place within the individual business units and functional groups (a distributed competency), while the more challenging Horizon 2 & 3 endeavors are executed by a centralized core innovation group acting under the direction of the Chief Innovation Officer.

It is helpful to understand also that innovation can and should originate from numerous different sources within the business, considering that there are three different strategic horizons to be addressed, and four different types of innovation that can be so leveraged (sustaining, breakthrough, disruptive, and transformative). The image below reflects a potentially ideal prototypical organization showing where each type of innovation might originate from in each case, as well as which functions focus on organic, extended organic (partnerships), and inorganic growth mechanisms.

Once this key decision has been made, the next step will be to define and build out the necessary team structures to ensure individual projects get championed and executed. Generally speaking, the structure of these teams will entail three primary roles – leaders, facilitators, and implementers. These are explained in more detail under Roles and Responsibilities.

The final step in the area of structure is to define the working relationships between the groups involved (e.g. core innovation team and front line business units) and the particular events at which formal interactions will take place and decisions made. These relationships can involve any number of structured and unstructured interactions, used as needed for each project (with generally no limit to how much informal interaction takes place). The guiding philosophy for these relationships should be one of stakeholder alignment, as the critical need will be to manage stakeholder expectations and get the right people on board with specific decisions prior to taking the next action steps. In terms of formal events, this may look like something like a traditional phase–gate process in which decision–makers convene, review insights and results to date, and make decisions as to whether to continue supporting specific projects, modify them, or shelve them, according to a predefined set of metrics and KPIs.

Just as with structures and processes, Corporate Innovation must establish a clear set of roles and responsibilities. The most important consideration here will be the selection of those leaders used to drive the program, at all levels – strategic, tactical, and everywhere between.

At the strategic level, Corporate Innovation requires its own seat at the C table – known generally as the Chief Innovation Officer, or CInO – as shown in the characteristic image below. This is to ensure it has equal footing and visibility with the organization's other functions and that it has a voice when needed, including at times being the most prominent voice.

The person who fills this role will become the business' Innovation Architect. As such, the position demands a particular type of executive – one who sees the big picture, one who gets the “round peg in a square hole” nature of innovation, and one who can convincingly articulate a vision and plan for moving the program forward, as well as advocate for its individual projects. There is a relatively small cohort of executive–level leaders who match this unique profile.

The actual role of the CInO can vary quite widely depending on the level of innovation maturity the company has reached and on how the CEO and Board of Directors wish to leverage the Corporate Innovation program. There are four generally–accepted functions that the CInO role can assume (each associated with a particular level of innovation maturity):

Advisor — This CInO serves as an internal consultant to the CEO to help focus the company on defining a series of innovation strategies, both overall and within individual business units. They scan the external environment and the company for new opportunities, and then based on the trends and changes they see, make appropriate recommendations. Actual execution of the innovation strategies generally passes to the front line business units. In effect, this CInO is the company's innovation function, consolidated into one person. They may work either in isolation, or as part of a Corporate Strategy group. Over time, this CInO may influence a broader journey toward a more comprehensive Corporate Innovation capability.

Catalyst — This CInO takes on the heavy–lifting task of initiating a new Corporate Innovation program, with the goal of institutionalizing systematic innovation capable of achieving short, medium, and long term growth objectives. This CInO must be an agent of change and a convincing evangelist at the highest levels of the organization. As such, the role requires a well–respected individual capable of building alliances and alignment among key business leaders, and of exerting significant influence when needed.

Expander — This CInO serves as a curator of emerging innovation capabilities within the business. Their task is to continue maturing the organization's innovation prowess and further systematizing the overall innovation process such that it becomes increasingly embedded inside the business. This CInO does very little in terms of setting actual innovation strategies, as that capability has by this point matured inside of individual business units and functional groups, including the core innovation group(s). Instead, they spend their energies developing increasingly advanced innovation programs and capabilities.

Renewer — This CInO — because the organization has reached the highest levels of innovation maturity — now spends their energies engaged with the CEO and Board of Directors developing higher level business strategies aimed at helping the company navigate ‘bends in the road’ it may encounter, thus constantly ‘renewing’ itself. This may involve some highly strategic opportunity changes for the company, together with significant changes in the company's architecture.

At times, and under certain circumstances, the role of the CInO may encompass aspects of more than one of these.

At a level in between strategic and tactical, one must consider the group of individuals who will lead and manage the Innovation Management system, which the program will by necessity need. This group – known generically as the Evaluation Group – serves as gatekeeper of the Innovation pipeline. They are charged with evaluating the steady stream of ideas submitted into the Innovation Funnel and selecting those ideas they feel hold promise. The members of this group must be experienced business leaders who have been explicitly trained and empowered to execute this role. These individuals can hail from any variety of corporate functions, including Corporate Strategy, Marketing, Engineering, business unit leadership, or an equivalent function. Regardless of how this group is constituted, it must function cohesively, and will need to maintain solid connections to, and relationships with, designated point–persons inside of each business unit. These individuals should otherwise not have roles inside of the business units or other functional groups. This is to ensure they remain unbiased toward maintaining a status quo of how things are currently done in the company.

Another important set of roles that operate at both the strategic and tactical levels is that of Marketing Communications specialists. These individuals run engagement marketing and public relations campaigns on behalf of the program, both internally and externally. Such campaigns help to drive engagement in the program by sending the right messaging, making this is a very crucial set of roles for the program. For more on this aspect of the program, see Public Relations below.

At the tactical level are the acting innovation teams – those teams tasked with championing and executing individual innovation projects. Specific roles have to be defined for these teams as well. They will generally involve three primary types of role – leaders, facilitators, and implementers. Leaders can come from any discipline. Their job is to both lead the project and champion it in all corners of the organization, up, down, and across, meaning they must be able to articulately advocate for the project's vision whenever and wherever that is called for. This requires a mix of entrepreneurial fervor, political savvy, and solid leadership skills. Facilitators are individuals who have been specially trained in the practices of innovation facilitation, such as Design Methods. Their job is to enable and facilitate the type of creative exploration work uniquely associated with innovation. Implementers make up the core cross–functional team that will carry out the hands–on work of each discipline, including such roles as Marketing, Engineering, Finance, Manufacturing, Sales, Customer Service, and so forth. Given their broad constituency, acting innovation teams require an equal mix of both hard and soft skills. In those cases where innovation is centralized into a distinct function, these three roles will generally be a part of that function. In contrast, wherever innovation is decentralized into the business units, the Leaders and Implementers will typically work for these business units, while the Facilitators may belong to a dedicated Innovation or Corporate Strategy Group.

The preceding sets of roles – CInO / Evaluation Group / MarCom / acting innovation teams – are representative of the types of roles that would be associated directly with the Corporate Innovation program. Aside from these, the next consideration must be for the roles and responsibilities that will reside inside of each business unit, where it is expected that certain business units will be the ones who take new innovations to market.

There are two critical roles that must be filled inside of each business unit. The first is the main point–person who will serve as the point–of–contact for communication on specific projects. This is largely a tactical role, and ensures that open communication and dialogue are constantly facilitated between Innovation Managers and the business unit. The second is the business unit champion – often the head executive of the business unit, or one of their next–in–command. This is a strategic role whose responsibility is to provide alignment with and support for specific projects – the so–called ‘downstream receiver’. Their job is to provide a go / no–go vote on specific projects targeted for their business unit, indicating which endeavors they intend to support and which they do not. This is very important, as otherwise innovation groups can end up working on projects that go nowhere and never get commercialized. Thus, the Corporate Innovation leadership must get this person's vote of support for an idea up front if they are to justify the time, effort, and resources required to develop the idea. In most cases, some amount of preliminary work will have to be done on each idea to get it to this point, at which point the ideas are then ‘pitched’ to the champion so that they can decide which ones they will support and which they will pass on. This is an integral part of the Innovation Management selection process, in which, at any given review, the champion will be reviewing a portfolio of projects at differing stages of development. These two roles – the point–person and the champion – are critical to the success of every Corporate Innovation program, and must therefore be defined inside of each front line business unit.

Finally, aside from the core innovation and business unit roles, in some cases special groups will be used to run special parts of the innovation program. This can include for example Open Innovation and Corporate Venturing partnerships. With Corporate Venturing in particular, if the organization intends to pursue this on a large scale as an ongoing vehicle of its growth strategy, it will typically set it up as a separate legal and financial entity with its own operating protocols. This allows the entity to make its own investment decisions without first having to obtain approval from the main business, enabling it to operate agilely. Its operation would therefore look more like that of a private Venture Capital fund than of a large business enterprise. Whenever special groups such as these are set up, their unique roles and responsibilities will have to be defined accordingly.

Once structures have been defined, it is next possible to define the actual governance processes, or more accurately, series of processes, the innovation program will use. Given that the broader program may incorporate a variety of activities involving any number of growth vehicles and any number of internal and external constituents, the details around each process can vary considerably from one to the other.

In order to think about overall governance, it is easiest to break the innovation process into its three stages – front end (ideation), mid zone (research and strategizing), and back end (development and implementation / commercialization). At each stage, a gating process will need to be used to move the most promising ideas forward, while rationalizing the rest (perhaps placing them into a ‘parking lot’ to be revisited at a later time). This process starts out with a funnel (widely capturing as many ideas as possible) and proceeds to a pipeline (those worth working on). Its management is similar to that of a traditional phase–gate process, except that in the case of new innovations the projects often end up having to be continually ‘pitched’ to decision–makers as they get further refined throughout the process. This process of managing innovation is well documented in the Market Stream IM System. Having a solid Innovation Management system in place will prove critical to maintaining support for the program inside the organization, as it gives participants a clearly understood process for getting their ideas introduced and having them fairly and objectively considered by the business. This will boost their morale and engagement in the program.

On the front end (funnel), new ideas can be captured and evaluated through the Innovation Management system. These ideas may originate from any number of sources, including, for example, individuals, internal ideation campaigns, external crowdsourcing, strategic think–tanks, or anywhere else (see Engagement below). Responsibility for capturing all these ideas and ensuring they get properly catalogued will fall to managers in the Corporate Innovation program. It is important they ensure that all new ideas, regardless of their source (internal or external), get catalogued and tracked in the IM System so that the program's overall effectiveness can be monitored. Corporate Innovation Managers will find internally–generated ideas from mechanisms officially tied to the program the easiest to capture and catalog, while externally–generated ideas from outside sources such as Open Innovation partnerships and CV–backed startups will be more challenging to capture and catalog, particularly when those areas are managed by separate groups. Nevertheless, it is important they capture and track these ideas, as they are often the ones that are so novel and foreign to how an industry works that they end up being the really impactful, even disruptive, innovations that matter the most.

In the mid zone (early pipeline), where projects have been vetted and certain ones selected for investigative and planning work (e.g. market research, developing go–to–market strategies, etc.), the process can be managed on the basis of whether the work is to be undertaken internally or externally. Internally, business plans are developed and pitched to a Selection Panel (aka ‘Angel Committee’), as explained in the Market Stream IM System. Externally, the process will typically involve outside parties doing most of the work, and then interfacing with key point–persons inside the Innovation Group or front line business units. The results of that work will also be pitched to a Selection Panel for further investment prior to commercialization. In the case of Corporate Venturing, the investment decision process is typically managed separately based on the perceived merit of a particular venture, and is generally overseen by a separate Selection Panel.

In the back end (late pipeline), where projects have been fully green–lighted for development and implementation / commercialization, development will generally take one of three routes, while commercialization will most often take place inside of a sponsoring business unit, particularly if it involves a new offering. In Route 1, the development integrates into the organization's standard New Product Development (NPD) pipeline or some similar pipeline (e.g. Manufacturing Process Improvement Team if the innovation involves a new manufacturing capability, or Sales Capability Team if the innovation involves a new Sales and Distribution process). In Route 2, the Innovation Group uses its own development team to develop the new innovation, more common where there is a new technology or new product category involved. In Route 3, the development is sourced to an outside third party. The decision as to which of these three routes to take will depend on the nature, scale, and scope of the project, and how well it otherwise fits with what a particular business unit may be doing and how they wish to pursue it. From an implementation / commercialization standpoint, if the new innovation involves a product or service offering, commercialization will generally fall back to a sponsoring business unit (unless there is no business unit aligned to it, in which case either the Innovation Group will commercialize it, or a new business unit will be formed to do so). If the new innovation involves a process (internal or external), implementation will tend to fall to an appropriate functional group, and will be implemented across most or all business units.

As seen, Corporate Innovation governance, and Innovation Management in general, have distinct processes for the front end, mid zone, and back end of the funnel / pipeline. So long as these are well coordinated, the program will yield a steady stream of results. One important consideration across all these stages is that the governance process operate on agreed–upon ground rules, and those rules are made widely known. This drives transparency within the program and across the organization. That in turn helps to maintain the health of the program by ensuring participants feel there is a level of objectivity in how it is managed.

In the course of carrying out Corporate Innovation, select sets of metrics and KPIs will be needed for governance purposes. Since innovation programs generally have many facets, these metrics and KPIs will fall into a number of different categories, each serving a particular purpose. Below, six such categories are highlighted, but in any given program there can be more or less than this, depending on the design and intentions of the program.

The first category of metrics will be those used to evaluate individual ideas and projects prior to and during early development. Typically each phase of the Innovation Management process (funnel / pipeline) will have its own sets of metrics. While the exact metrics may vary from one business unit to the next, according to their particular needs, the metrics should nevertheless be applied uniformly across all the ideas and projects so as to drive objectivity and transparency in the process (important for keeping positive morale in the program). Examples of possible metrics might include: degree of alignment to BU strategy, ability to create new value platforms, expected revenue over the first 5 years, line extension options, implementation costs (to develop / produce / market / sell), financial returns (e.g. ROI, DCF / NPV), development lead times, commercial risks, technical risks, and so forth. These are not unlike the metrics used in normal product roadmap discussions, except that since the ideas are typically more ‘outside the norm’, the confidence around their projections may be somewhat fuzzier (though this should not be seen as a roadblock).

A second category of metrics is those used to evaluate insights gained from market research. Their purpose is to judge whether or not the research indicates acceptable viability of a particular concept, such that further research and/or development is warranted. Since market research will be conducted for only a select few concepts, the need for uniformity here is less pressing; the most important consideration will be to ensure that the metrics or KPIs are well–suited to the situation and to what needs to be learned about the concept.

A third category of metrics is those used to evaluate the learnings from in–market testing conducted in select test markets. The purpose of these metrics is to gauge whether or not these tests indicate a level of market viability and scalability that will prove attractive to the company, and if it should therefore move forward with a full market roll–out. Since there will only be a limited number of market tests conducted, the need for uniformity here is less pressing; the most important consideration will be to ensure that the metrics or KPIs are well–suited to the situation and to what is attempting to be demonstrated about the concept.

A fourth category of metrics is those used for Corporate Venturing decision–making. These are used to gauge the expected success and growth of a particular new business venture such that decisions can be made around whether or not to invest, when to invest, how much to invest, and how much to otherwise get involved in each new venture. Typically, different metrics will be used depending on the growth stage of the venture and the degree of alignment it has with the organization's core business strategy.

A fifth category of metrics is those used to evaluate the final success of individual innovation projects. These can be any standard business metric, such as real revenue growth, margin realization, brand uplift, regional sales volumes, actual versus planned costs, impact elsewhere in the business, and so forth. Each project will be judged against its originally forecasted / expected success parameters (those established in the first category above).

A final – and very important – category of metrics is those used to assess the health and effectiveness / success of the Corporate Innovation program itself. Particularly as the program begins to enter into its third, fourth, and fifth years, there begins to develop some clarity around its overall level of effectiveness in driving new innovations that have meaningful impact to the business and its markets.

Often this set of metrics is broken down into approximately eight areas, as follows:

These metrics are sometimes clustered into three groups, namely:

Needless to say, there are a large number of metrics that one can use to assess their program's health. The important consideration is for managers to use those that are most meaningful to their business and that will drive momentum toward the desired behaviors and outcomes in the business.

In order to ensure that those charged with leading and operating the Corporate Innovation program are capable of doing so, it will be necessary to establish an appropriate program budget. This budget will cover the salaries and overhead of all those officially assigned to operating the program, as well as the necessary overhead costs of operating facilities like Innovation Labs and so forth. It will often also include a Training Budget to cover the cost of sending the business' staff to innovation training and securing formal certification in this area.

This budget must also take into account the fact that much of the innovation work associated with the program will involve extensive upfront experimentation so that it can learn and decipher the emerging market needs it is to work with. Such work should be viewed as a necessary ongoing investment in the program.

Ultimately this budget will need to cover the Enablers presented further below, which will include such items as training, certification, enabling technologies (for example, design software), labs, equipment, and other infrastructure, subscriptions to syndicated market analysis and futures forecasts, and so on.

Also, if there are major capital expenditures to be made on behalf of the program, such as when first building and outfitting a new Innovation Lab, those must also be taken into consideration. This will require that they be allocated, dispensed appropriately, and once the assets are in operation, amortized appropriately through depreciation accounting.

In order that a selection of innovation projects can be executed under the program and thus taken to fruition, it will be necessary to establish an appropriate pipeline budget. This is the (sometimes rather substantial) budget that will be used to invest in developing and launching certain new innovations for the business.

This budget should be sized according to the program's required outcomes and with an understanding of the types of growth vehicles the program will leverage (see the GR5 Roadmap). In particular, many of the long term vehicles such as Corporate Venturing may require relatively large budgets if they are to be successful.

In most situations, it will prove beneficial to establish separate budgets for Horizon 1, Horizon 2, and Horizon 3 investments, so that these initiatives do not compete with one another for the same budget (in which case Horizon 1 projects tend to win out a disproportionate amount of the time). Most Horizon 1 endeavors will be run inside of established business units, whereas most Horizon 2 and 3 endeavors will tend to be run in a centralized Core Innovation Group or Core R&D Group. In either case, the business should establish how it intends to apportion its overall investment budget so that it can drive the short–term, medium–term, and long–term elements of its Innovation Portfolio according to its governing Innovation Strategy.

Regarding budget management, the Corporate Innovation program should be managed using a 3–year rolling budget with quarterly reviews, as opposed to a fixed annual budget. This is because many things will be learned each quarter and numerous things will change from quarter to quarter, such that the budget will need a certain level of running flexibility. This allows the program to remain agile and its funds to be shifted from place to place as promising new opportunities are discovered that need to be pursued aggressively. It also allows the program to adjust in accordance with changes in the company's broader business strategy so that it is always in sync the rest of the company.

To the extent that the Innovation Strategy calls for making external investments in the pursuit of new innovation capabilities – such as through Corporate Venturing or M&A – the organization will need to set aside and properly manage a separate budget for this.

Whenever Corporate Venturing is to be pursued extensively, the enterprise will typically set up an independent Corporate Venturing arm. This is a separate legal and financial entity with its own Board of Directors and its own balance sheets, separate from those of the primary organization. This allows for investment decisions to be made and managed autonomously.

In any given Corporate Innovation program, if the organization's participants do not understand how to go about pursuing innovation, and if they are not given the tools and resources they need to be effective at innovation, then the program will not get particularly far.

For this reason, it is critically important to give participants the training they need to think and act ‘like innovators’, and access to the tools and resources they need to be effective at innovation. This includes fresh new business insights that can point their compasses in a meaningful direction, tools to analyze and qualify new opportunities, mentors who can help point them in the right direction and impart forward momentum, places to work that inspire innovation, and time to pursue innovation... time that is explicitly set aside for this purpose. With these resources at their disposal and the right training on how to use them, the Corporate Innovation program can sustain high levels of engagement and yield some particularly high–return outcomes.

Within most Corporate Innovation programs, there are usually multiple levels of training, and with this, various levels of certification. These certifications often mirror those seen in Six–Sigma programs, e.g. Green Belt, Black Belt, and so forth. Using certifications at different levels helps in two ways. First, it helps to reinforce in participants' minds the value the organization places on innovation and on the innovation program. Second, it helps people know who are the highest level innovation experts, giving them go–to people to consult with when certain insights are needed. Both of these can play an important role in driving engagement and helping to support the program's ongoing health.

Good innovation work, whether or not in the context of a Corporate Innovation program, always begins with effective discovery and insights–mining work.

Corporate Innovation programs, in particular, are starved for these discoveries and insights broadly across the enterprise. Across all the parties who have to contribute new ideas, evaluate and select new ideas, and/or execute new ideas, solid market intelligence and user insights are a must. This is so that they can build high confidence in what is being pursued.

Therefore, if a Corporate Innovation program is to produce outcomes that meaningfully impact the business and its markets, it has to provide the necessary mechanisms and resources for facilitating discovery work, and for mining relevant insights (e.g. user research laboratories, market research groups, and trend–scouting teams).

For the current Foundations of Value (H1), this may revolve mostly around user research to more deeply uncover currently unmet needs and to validate proposed solutions around those needs. For emerging Foundations of Value (H2 and H3), this may revolve mostly around trendcasting, trend analysis, futuring, and scenario planning.

All of these will prove critical to facilitating the discovery and insights work needed for successful Corporate Innovation.

Any good Corporate Innovation program – if it is to be effective – will have to provide the organization with certain resources and facilities so that its members can pursue the work needed to produce useful innovations.

This will require they make certain investments in technology and infrastructure.

The technology side largely involves any of the tools associated with facilitating innovation. This will include, for example, creative design tools such as Software Development Environments, Computer–Aided Industrial Design, Electrical CAD, and Mechanical CAD. It will also include Idea Management software, Portfolio Management software, team collaboration and sharing platforms, and various project management tools. It can also include any special capital equipment that is germane to the enterprise's efforts, such as rapid prototyping (3D printing) machines, maker labs, various scientific and engineering test equipment, research libraries, and so forth.

The infrastructure side largely involves various collections of laboratories, research spaces, study spaces, team coworking spaces, and access otherwise to particular places and resources conducive to the innovation work. It also includes access to networks of businesses, partners, and individuals, and to certain online resources. It is important that the laboratories are able to simulate real world environments as closely as possible, so that members can conduct an unlimited array of ‘what if’ tests, including with real subjects on site.

The right technology and infrastructure are always necessary ingredients for an effective and successful Corporate Innovation endeavor.

A well–functioning Corporate Innovation program requires healthy networks and ecosystems.

Networks involve the collection of personal and corporate relationships that exists among a wide variety of internal and external resources. They are about ‘who knows who’, ‘what company knows what company’, and ‘who knows where to get X’. The broader and more diverse these networks are, the healthier they are, and the more they will benefit the innovation program. They benefit it by creating access to knowledge, insights, and resources that may otherwise be, for all intensive purposes, inaccessible. These are often resources that end up benefiting various innovation projects and initiatives in unexpected ways, particularly as the organization seeks to cross–pollinate business models and other practices. In particular, individuals can tap into others in their networks to solicit their perceptions of new problem spaces (and thus innovation opportunities) they are seeing, or to solicit their opinions of specific solution concepts they are considering. This sort of network feedback – especially when sought out with breadth and diversity – can often prove crucial to launching successful new innovations.

Ecosystems refer to the broad support systems that a business has in place – largely external – for helping it get certain things accomplished in the marketplace. This can be business partners, suppliers, consultants, service providers, regulatory groups, investors, customers, and so on. Particularly whenever these resources are aligned around new ways of operating that facilitate new business models and new value propositions, they can play a powerful role in making new innovations happen, and should thus be leveraged liberally to meet evolving market needs.

Without healthy networks and ecosystems, any given enterprise's innovation efforts will likely come up short and not be nearly effective as they would be otherwise. Having these support systems – particularly on the outside – can often mean the difference between success and failure for a number of endeavors. Also, it is not uncommon for these extended ecosystems to end up becoming the ‘shelter for homeless ideas’... things that just don't fit today's organization, yet represent potentially major elements of tomorrow's organization. Thus they are crucially important for helping to future–proof the business.

Engagement is foundational and absolutely critical to an innovation program's success. It is what democratizes the program and connects it with the people who will give it life. It is also what ‘feeds’ the program's pipeline with innovative new ideas. Without engagement, the program is effectively dead.

To this end, a Corporate Innovation program must employ what is known as mechanisms of engagement. These enable the program to tap into the insights, knowledge, and perceptions of the organization's internal staff and external partners, primarily around what is happening externally to the business, in current and potential markets, and, very importantly, how they can potentially capitalize on those things. In some cases, they actually involve creating something to bring to market.

There are numerous mechanisms of engagement in common use for Corporate Innovation programs. Each of these serves a different purpose and has an appropriate time and place, according to the needs of the program at any given time. Each also has a very different way of engaging people, and therefore a different feel. Some are simple, straightforward, and unstructured, while others are more structured and very work–intensive. For this reason, some mechanisms will resonate with certain people more so than with others. This is why programs will generally need to use a variety of mechanisms.

The following is a brief explanation of select mechanisms of engagement:

Communities of Practice — These are ongoing communities of professional peers organized around specific domains, or subject matters. User Groups are a very common form of these communities, as with, for example, a software platform users group. They are formed to enable individuals to share their expertise in certain areas and to help out one another opportunistically, which generally means as needs and interests arise. As such, they help to stoke occasional inputs into the Corporate Innovation program. Just as importantly though, by sharing openly and widely, they help further the organization's capabilities in these areas. Since these communities are ‘open–ended’ in nature, there are no set timeframes for follow–on action. In order to be self–sustaining, each community will need a distinct subject matter with broad interest and a community manager.

A similar concept is that of ‘Communities of Passion’, which are often seen in the case of Owners Groups like those that form around iconic brands like Apple, Harley Davidson, Corvette, and so on. These groups, too, can spawn new insights into possible new opportunities to pursue.

Expert Forums — These are online forums designed to allow individuals and teams to submit their questions on particular topics and get back answers and solutions from subject matter experts. The subject matter experts need not be internal; they can just as well be outside experts sourced from any number of places, including venues such as online Open Innovation and Subject Matter Expert portals. The insights and ideas they generate can produce useful fodder for the Corporate Innovation program. These sometimes require an extended period of promotion to get people in the habit of using them and making them an ingrained part of how they routinely find answers.

A well–known example of a panel–format forum is the Newsweek Expert Forum. Well–known examples of individual expert forums include Thinkers360, Gerson Lehrman Group, Guidepoint Global, Coleman Research, Maven, and Zintro.

Speed Dating — These are scheduled sessions between peers (typically two, sometimes three) designed to facilitate reciprocal sharing of insights, expertise, and experience. They are much more intimate and ‘on–topic’ than are Communities of Practice. Speed dating can be productive at any level of the organization, but can prove particularly effective at higher levels, where individuals often have deep wells of business expertise around specific functional domains. Speed dates may happen only once, or they can become recurring if desired. With speed dating, it is important to properly scope the participants so that each side understands the give–and–take they should expect, and therefore have bought into the idea so they are prepared to engage in it completely. The outcomes of speed dates can often produce extremely valuable inputs into the broader innovation program, and may result in any manner of innovation initiatives for the business (some of which may have immediate impact). Speed Dating in this context is also known as ‘Speed Networking&rsquo.

Idea Conferences — Also known as ‘Idea Accelerators’, these are outside conferences that participants are sent to so that they can be exposed to fresh thinking and diverse ideas from all over the world. They allow these individuals to not only hear the ideas, but also network and interact with the presenters and other attendees to further explore and develop some of the ideas. They are like speed–dating on steroids, all crammed into a short time span. Examples of such conferences include TED, the Aspen Ideas Festival, and Davos (the World Economic Forum's annual meeting). Participants typically return to their offices inspired with all manner of new ways of seeing and thinking and with ideas that can be applied inside the business. Ultimately, some of these ideas will make their way into the Innovation Funnel.

Maverick Panels — Also known as ‘Thought Leader Panels’, these are events where external ‘thought leaders’ (some of whom should be mavericks and provocateurs) are brought in to meet face–to–face with the company's leading innovators. The external thought leaders / experts are generally considered visionary in their respective fields, such that they bring in fresh new perspectives and insights that should ideally challenge and stretch the organization's thinking. Here they discuss, explore, speculate, and otherwise engage in very active and sometimes vociferous debate amongst the panel. Beyond the discussion and debate, they can also engage in active exploration of future scenarios together, as well as co–creation of concepts for new businesses, offerings, and business models that stand to capitalize on the intersection of certain trends and their insights. Given their vociferous nature, these are very different than a ‘gentlemen's debate’, as they are intended to move the needle on the organization's thinking in a significantly meaningful way.

Cross–Industry Lateral Innovation Panels — These are private groups of businesses from different industries who from time to time host panel sessions together in which each business sends one or more leaders to engage with their peers on the panel. The purpose of these panels is so that these businesses can cross–pollinate ideas with one another and in some cases address a particular challenge that one or more of them wishes to address. Depending on the panel and how it tends to operate, its sessions can either be highly structured (usually as workshops), or more unstructured (usually as simple open dialogues). Because these businesses all come from different industries, these panels tend to produce highly lateral thinking around different ways of seeing things and doing things – what are known as lateral approaches. After each panel session concludes, these business leaders can then return to their respective organizations and use the new insights they gained as fresh new fodder for their business' innovation program. Cross–Industry Lateral Innovation Panels tend to be formed and run as loose partnerships, with member organizations joining and leaving as their needs would dictate. Any given business can therefore set up and run their own panel as they wish. Because they involve sending business leaders outside the organization to source potential new ideas from other businesses, these panels are also considered a form of Open Innovation.

Innovation Mentors — Also known as ‘i–Mentors’, these are individuals who have been specially–trained as innovation mentors / facilitators and who float around the organization, moving from place to place as needed or requested. They plug themselves into select project teams and deploy various innovation tools (e.g., problem reframing, brainstorming, business model canvas, customer journey mapping, etc.) to help the teams break out of current thinking patterns around a challenge and tap into new thinking patterns. This often yields new insights into the more fundamental problem, which in turn yields novel and innovative solutions, producing positive results for the innovation program and the organization.

Individuals certified by GInI as Certified Design Thinking Professionals (CDTP®) and Certified Innovation Strategists (CInS®) make for excellent Innovation Mentors inside business organizations. See GInI Professional Certification for more on these.

Independent Research Projects — These are short–term loosely–structured projects — typically lasting from 3 to 6 months in duration — in which either an individual or a small team of 2 – 3 persons undertakes — outside of their normal work duties — a special research study aimed at identifying, clarifying, and justifying a particular new opportunity for the organization to pursue. This would include the nature of the opportunity (the problem or challenge it is addressing), who it is targeting (its target markets and customers), why they have this need, how long they have had this need and expect to have it in the future, the new innovation that is proposed to address the need, why this new innovation is believed to be the best way to resolve that need, what about this new innovation and its message will compel those customers to adopt and use it, how the organization will take it to market, how much revenue the organization is expected to make from it (or how much social and/or economic impact it is expected to produce in the case of public sector and non–profit organizations), how much it will cost the organization to produce and deliver it, the resultant profits it will generate as it ramps up over a period of time, and the resultant return on investment for the organization. Once completed, this individual(s) will submit their final report on the project, together with their recommendations as to whether or not it should be pursued, to the appropriate decision–makers in the organization. In exchange for completing these projects, these individuals will receive special recognition in their next performance reviews, which may improve their chances of receiving a promotion and/or raise in the organization, particularly if the study and report were done well, and especially if the study leads to a promising new endeavor for the organization.

Ideation Challenges — These are crowdsourced ideation campaigns focused on a specific business challenge. They are presented to a wide and diverse audience over a limited timeframe, and have clear follow–up milestones. They sometimes use gamification to drive participation, where peers can ‘vote up’ or ‘vote down’ one another's ideas to see who's ideas rise to the top, and who's sink to the bottom, there being prizes for those that float to the top. Idea Challenges may generate hundreds of new ideas, each of which must then be reviewed and evaluated for its value and actionability. Follow up is usually assigned to select teams either in Corporate Strategy, Corporate Innovation, or one of the front–line business units.

Innovation Kits — This is an exercise in which any number of participants from all over the organization are provided with carefully–designed starter kits containing various paraphernalia. The paraphernalia are meant to serve as thought sparkers. Examples might include booklets on how to identify and study unmet needs, blank credit cards to spend on their research and experiments, and so on. Participants are challenged to take the paraphernalia and use it to spark innovative new thinking around a particular business challenge of their choosing, and to consider how the various pieces and parts might be rethought and recombined in novel ways to generate novel new ideas about needs, opportunities, and solutions. The end result is the submission by participants of new ideas they were able to generate from the synthesis of the different starter pieces around new opportunities for the organization. There is no limit to how many innovation kits can be handed out, nor on how long such a campaign can be run at a given time. And while it may prove useful to have all the kits be uniform in any given cohort, it is often good to mix up the kit contents over time, as this will generate the greatest possible variety of new ideas over the long run. The organization can also sponsor a Second Stage Innovation Kit for those whose new ideas are accepted at the end of Stage 1 — so that they can help the organization pursue the idea even further, perhaps even proceeding to a Third Stage Innovation Kit to really move the concept ‘over the line’ and toward eventual full implementation and deployment.

By far the most famous and well–known Innovation Kit is that of the Adobe Kickbox, which Mark Randall, then Vice–President of Creativity at Adobe, introduced there to eliminate much of the friction of getting new ideas funded and supported — placing a thousand little bets rather than just a few big ones, and thus truly awakening the company's intrapreneurs. The Adobe Kickbox starts with a red box in Stage 1, and – for those new ideas accepted – proceeds to a blue box in Stage 2 and thereafter a yellow box in Stage 3. Kickbox was first introduced at Adobe in 2012. By autumn 2014, hundreds of company employees had taken part in the program (which includes two days of training) and 22 individuals and teams had reached the ‘blue box stage’ – where further access to funding and venture development coaching is provided. Kickbox was quickly adopted elsewhere and spread like wildfire. It was so popular in fact that it spawned its own foundation – The Kickbox Foundation (now led by Mark Randall) – to further promote and advance it as a powerful tool for innovation. A well–known derivative of it is the Swisscom KICKBOOK. The Kickbox kit can be secured from the foundation, as well as full instructions on how to build your own kits from scratch. Refer to www.kickbox.org.

Innovation Workshops — These are hands–on working sessions purposefully–designed to engage participants in a variety of thought–provoking activities around discovery and creation. They come in a variety of forms, each designed to accomplish a specific purpose and to engage a specific type of participant from the organization (see our Workshops, Events, & Fieldwork site for clear examples). Regardless of which workshops are used, they will all yield actionable fodder for the innovation program — some ideas being strategic and some being tactical, but all being valuable.

Hackathons — These are team challenge sprints organized to build something entirely new in a highly–compressed timeframe (for example, over a weekend). They are most common in the tech / software worlds. They can be a great source of fun for those inclined to participate, and often produce a highly useful outcome in record time. The challenge becomes how to finish what the event began and turn that into a finished product since the outcome rarely emerges in salable form. That work must typically be transferred to a formal development team who will complete and implement the outcome. Keeping the momentum to ensure this happens generally requires some type of executive sponsorship with a commitment to finish what the hackathon began. With the right follow–on, these have been known to have business impact in as little as one month, particularly when the outcome can be integrated into something that already exists.

Flash Builds — Modeled after the concept of

A well–documented example of a Flash Build is the one done by a team from Nordstrom Innovation Lab in 2014 at its flagship retail store in Seattle, Washington, USA, where in one week the team developed an iPad–based sunglass comparison app for shoppers. The video of this Flash Build can be watched on YouTube at this link.

Design Sprints — Originally developed by GV (formerly Google Ventures), Design Sprints have become a popular fast–concept–validation method for new digital solutions. The sprint involves a five–day process aimed at answering critical business questions, which it does by rapidly designing, prototyping, and user–testing the new concept. GV refers to it as a “greatest hits of business strategy, innovation, behavior science, design thinking, and more, all packaged into a battle–tested process that any team can use.” The Design Sprint takes place as follows. On Day 1, the team maps out the problem they are attacking and picks an important place to focus their efforts. On Day 2, the team sketches out competing solutions on paper. On Day 3, the team makes the difficult decision of which solution to pursue, turning their ideas into a testable hypothesis. On Day 4, the team cranks out a high–fidelity prototype of their chosen solution. And on Day 5, they test this new (prototype) solution with five real live users. So instead of waiting to launch an eventual MVP to understand whether or not their idea is a good one, working together in a sprint teams are able to compress what might otherwise be months of development and validation time into a single week. They end up with a functional prototype which they test with real users on the spot, affording them clear insights into the validity of their hypotheses, and thus short–cutting what otherwise might be a potentially endless debate cycle. This allows them to, in effect, fast–forward into the future to see what their finished product will look like and what customer reactions to it will be, prior to making any expensive commitments such as a VC investment. Design Sprints can thus be a highly valuable tool for rapidly validating new business concepts.

Design Sprints were created by Jake Knapp while a Design Partner at GV and explained in his 2016 book Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days (Simon & Schuster, 2016).

Innovation Jams — These are open discussion and brainstorming forums framed around some issue that is pertinent and relevant to the business at the time. Using various mediums, they serve as a means for broad scale collaborative innovation. Given their potential scale, they are generally curated and moderated by a trained moderator. They allow participants from the broadest possible global audience — often numerous countries and companies, and potentially thousands of individuals — to share their insights, perspectives, and ideas on an issue, with the goal of discovering new solutions to the problem (often a long–standing problem). Because of their ability to integrate so many diverse perspectives, they have shown themselves to be a powerful tool for seeing problems with ‘new eyes’ and creating solutions that no individual or group ever could have in isolation. In the context of a Corporate Innovation Program, Innovation Jams can be a powerful tool for generating well considered new business ideas, perhaps in response to a challenge or opportunity that was first identified elsewhere in the program.

Possibly the most well–known example of a broad scale innovation jam was

IBM's 2006 Innovation Jam™, which brought together more than 150,000 people from 104 countries and 67 companies and resulted in launching 10 new businesses using $100M of seed investment. See more at www.collaborativejam.com

SWICH – The Six Week Innovation Challenge — These are individually structured, but otherwise unscheduled, team opportunity identification / evaluation / justification exercises lasting precisely six weeks long each. Here, a cross-functional team – usually of around 5 – 7 individuals – forms around a particular new idea they have and wish to develop, and thereafter seeks management approval to undertake a first SWICH sprint on it. In that six–week time period, they will allocate one full, entire day every week to work together on studying the new opportunity and testing very specific hypotheses around its failure hurdles so as to learn whether or not each such hurdle can be overcome. At the end of each six–week sprint, the team will present its findings and recommendations to the appropriate decision–makers in the organization. The goal – depending on the specific insights learned – is to either obtain approval to pursue yet another six–week sprint in order to develop the concept even further, or else have the effort killed altogether. If a team is given the green light to proceed, then it would once again repeat this six–week SWICH cycle, working together on the project one full day of each week to develop the concept yet further. If, after several such successful SWICH sprints, the concept still appears viable and interesting to the organization, then it may ultimately be adopted for full development and implementation by the organization.

The power of the SWICH stems from its three core ingredients – namely:

A) It brings relentless focus on proving the potential value of a concept through real market feedback.

B) It secures justifiable and sustained capacity for its development, in terms of time, attention, and capital.

C) It creates true management commitment to the innovation, even at the expense of the organization's day-to-day operations.

In the first case, each SWICH formulates the most impactful assumptions surrounding the new innovation. Those are turned into either a ‘feasibility hypothesis’ (we can get it to work) or a ‘value hypothesis’ (customers will adopt it and use it). By ranking all such hypotheses on their impact to success, the team discovers which are the biggest failure–factors for this innovation. Such hypotheses would be the first to be validated through real market feedback, using the Lean Startup build–measure–learn sequence.

In the second case, because SWICH team members allocate only one day per week in order to manage this effort inside their regular work schedules, it permits them just enough time to actually build and test a measurable ‘next step’ for the innovation; plus it also allows for the time needed for partners and suppliers to deliver their part of it, as well as the time needed for running certain tests. It likewise allows management – at each six–week milestone – to evaluate the value spent against the probability of continued success — all based on real market feedback. From this, they can decide to spend an exact known amount (in time and possibly capital) on proving out a well–defined next step in the innovation's development. SWICH thus presents a clear investment with manageable risk against only a minor disruption in current operations, plus a decision that can be explained transparently to all affected stakeholders.

In the third case, SWICH recognizes that most innovations which fail don't do so because they couldn't be developed, but rather because they were never fully adopted by the market, and so it purposefully addresses that issue by regularly focusing attention not on the biggest success–factors, but rather on the biggest failure–factors. Every six weeks, when pitching their work to date and asking senior management for approval on their next six weeks of work, the team is not emphasizing the next great feature it will create, but rather the next biggest hurdle it will overcome to make the innovation a business success. Indeed, if one does not address the biggest hurdles first, then all other development costs will have been wasted when it turns out later on that a certain hurdle couldn't be overcome. Thus, the focus of each SWICH is not on creating an innovative product or service, but rather on proving that there is nothing stopping the organization from getting the underlying business mechanism to work. Every pitch that demonstrates a successful step in the development of this new business mechanism broadens the support for, and commitment to, the concept, thereby allowing management to allocate valuable resources to it — resources that are otherwise being vied for by other endeavors in the organization.

SWICH was first used in 2017 in the oil & gas company Gasunie in The Netherlands. It was subsequently codified by Arent van ‘t Spijker in the 2019 book Continuous Innovation (Technics Publications, 2019), as part of his Continuous Innovation Framework, or COIN. Spijker describes it as… “a simple yet effective blend of an Agile sprint, Lean Startup, and Value Proposition Design, and it solves one of the most persistent problems in corporate innovation: a lack of dedicated resources for a continued period of time.”

Innovation Tournaments — These are prize–based contests designed to generate a large number of high–caliber new ideas (about new opportunities for the organization) in a set timeframe (the ‘best new idea for x’). They are often open to the general public and/or a large internal/external pool of participants. Being a force–ranked competition, they have competition–style rules and clearly defined participation guidelines, as there will inherently be ‘winners’ and ‘losers’. Their biggest challenge lies in generating the desired caliber of participation and from this the desired quality and caliber of new ideas. In the context of a Corporate Innovation Program, they can be a highly effective tool for generating high–quality ideas with which to front load the Innovation Funnel.

One of the most famous and popular Innovation Tournaments has been that hosted by the technology firm Cisco — originally dubbed the Cisco I Prize, and now called the Cisco Global Problem Solver Challenge. Learn more about this tournament at cisco.innovationchallenge.com.

5 x 5 Team Competitions — These are internal competitions aimed at generating a large number of relevant hypotheses about a particular business situation and with them a large number of high–quality, low–cost, quickly–executable business experiments designed to yield definitive learnings about the hypotheses. To accomplish this, the competition builds out approximately 5 teams, each comprised of approximately 5 members who have been explicitly hand–picked for this exercise, and then each team spends roughly 5 days together (full time) to develop what they believe is an important hypothesis (or several themed hypotheses) around their situation and with that 5 business experiments that can each be run within 5 weeks or less, and for $5,000 or less, which will yield useable and actionable insights about this hypothesis. At the end of the initial conception period, each team presents their hypothesis and their 5 proposed business experiments to a committee that ideally includes business unit leaders who can fund those experiments. Coming out of the competition, certain experiments will be funded and run, and select prizes awarded to winning hypotheses / experiments, according to the committee's final recommendations. These experiments do not generally yield final answers about solutions, but they do tend to confirm or repute particular elements of the hypotheses, and in so doing point the organization in the right direction for additional learning and possible solutions. More often than not, these experiments provide useful learnings that eventually do inform new innovations offered to the market. As a mechanism for exploring and testing various market hypotheses, 5 x 5 Team Competitions are highly compatible with Design Thinking methodology.

The concept of 5 x 5 Team Competitions – as described here – originated with Michael Schrage of the MIT Media Lab. It was explored in his 2014 book The Innovator's Hypothesis: How Cheap Experiments Are Worth More than Good Ideas (MIT Press, 2014).

Design Challenges — These are structured competitions in which rival teams tackle a common challenge to see which team can come up with the best solution design. These tend to generate lots of buzz and energy amongst the teams, as each team strategizes and then creates its own design (often spying on the other teams in the process). Often the challenge itself represents some type of breakthrough innovation… perhaps something that has never been done before (which makes success all the more amazing). Design Challenges not only unleash the power of competition, they truly help to engage participants very deeply into the process; typically no team member will be left a passive observer. Once the challenge is over, it is always interesting (even for the whole organization) to look over all the different designs and see how each team has approached the challenge. This can spur any number of other new ideas in the organization that themselves lead to new innovations.

In addition to private design challenges inside organizations, there are also some very famous, highly–publicized public Design Challenges as well. The most famous of these is the X Prize competition, aimed at tackling really big audacious challenges such as space flight, moon robots, hyper-efficient cars, massive carbon removal, and even genomics. It is run by the X Prize Foundation, led by well–known Futurist Peter Diamandis. Learn more at www.xprize.org.

Business Plan Competitions — Also known as ‘Shark Tanks’ in the US, and ‘Dragon's Dens’ in the UK, these are internal competitions in which teams of peers work together to, in each case, identify a new opportunity for the organization, develop a relatively complete and well–thought–out business plan for addressing it, and then pitch that plan to an internal venture board, generally in an attempt to get funding for it. This is not unlike what entrepreneurs do on the outside when pitching to Venture Capitalists for funding a new startup, except that in these cases, it is all internally–focused — the individuals are intrapreneurs pitching to an internal venture board for internal funding to develop a concept for use internally by the organization. Otherwise the vibe is very much the same. There are usually cash prizes and other incentives for the winners and runner–ups. In the context of a Corporate Innovation Program, these competitions provide an excellent tool for surfacing and funding many non–core, and potentially disruptive, business innovations. In some cases, they are also used as the venue for a formal intrapreneurship program. Considering the amount of (volunteer) work that teams have to invest into these competitions, companies typically host them only once or – at most twice – per year.

After the competition, the winning teams are typically given a Series A round of funding to further investigate, research, and otherwise prove out their concept and business plan. If that phase proves successful, then they may be awarded a Series B round for additional proof–of–concept development / testing, and so forth. If the concept proves strong enough, it may ultimately make its way all the way through to deployment (commercialization) within one of the organization's business units (either an existing or a new one). Depending on the scope of the concept and how much follow–on development work is required, business impact can be on the order of months to years.